The Ecology of Neopia

by parody_ham

--------

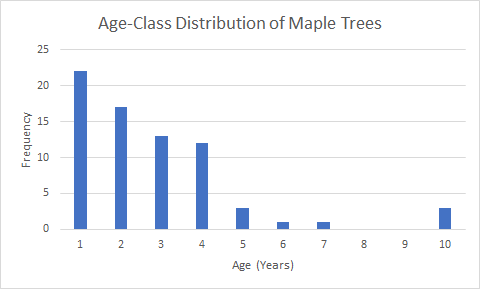

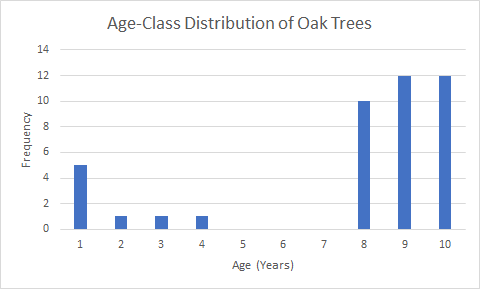

The land of Neopia is vast and wondrous, with countless mysteries waiting to be solved and incredible discoveries happening every day. Welcome to another edition of “Science with the Seekers,” where scientists from around Neopia share their expertise with the world. As this is a collaborative effort, Neopians involved will be listed in the acknowledgements at the end. What is Ecology? Put simply, Ecology is the study of how organisms interact with one another and their environment. There are multiple tiers of this scientific study, but we will focus on four of them today: organismal, population, community, and ecosystem. Each of these tiers build upon one another and grow in complexity with each jump. Organismal Ecology Organismal Ecology is the study of how a single organism interacts with its environment. More specifically, the adaptations that allow it to survive. We’ll focus on a few Neopian examples, namely the Bori and the Buzz, two opposites in this spectrum. Bear in mind that both of these examples have exceptions. For example, Ice Buzz and Fire Bori follow the opposite trends. The Bori: Built for the cold, this species of Neopet is hardy. Thick fur covers much of their body to retain warmth in even the harshest of days (temperatures of -50C have been recorded near the peak of Terror Mountain). Additionally, this species has armour-like dorsal (back) plating to aid in deflecting wind. Both of these are considered anatomical adaptations for heat retention. Bori tend to be short-legged and spend much of their time close to the ground as a means of reducing heat loss from convection (i.e. the wind stealing heat from their body) and have physiological (internal regulatory) mechanisms to reduce heat loss through something called “countercurrent exchange.” This process works by having blood vessels leaving the heart (where blood is warmer) being tucked next to the veins that are returning to the heart. It’s almost like a keeping a cup of hot cocoa next to the veins so that they can maintain their warmth by proximity. Finally, Bori use their long claws to dig burrows. These burrows are hideaways away from the wind, cold, and snow, which provide a safer, stabler environment for them to stay in. This species is an endotherm. In other words, they are “warm-blooded” and maintain a constant body temperature of around 36C (or 97F). But with all adaptations, there are benefits and down sides. One benefit is the ability to survive well in colder environments, but one down side is the amount of energy such an adaptation requires. Ignoring hibernation or torpor (which is a sort of short-term metabolic pause), Boris require at least one solid meal a day to maintain their internal temperatures, especially when exposed to the extreme cold. Some Terror Mountain-based companies have started selling high protein meals for cold-dwelling species such as Bori to help them tolerate the conditions, especially if their work requires long days. The Buzz: A tropical species, the Buzz has large, thin wings built for speed and manoeuvrability. This anatomical adaptation works well when avoiding any hungry beasts or dodging the vines, brambles, and thick forest understory common in dense, diverse tropical ecosystems. Their wings have an additional physiological benefit: heat reduction. The large surface area of their wings allows for heat to dissipate, thus keeping their core body temperature from getting too high. Minimum heat is required for Buzz to maintain consistent flight without significant effort, but too much heat can be problematic as well. Proper regulation is required to maintain basic functionality. Unlike the short, near-ground Bori, Buzz are tall, and most have bodies with a large surface area to volume ratio (i.e. more of their area is in contact with the environment). On colder days, Buzz are known to bask in the sun to reach optimal temperatures (more modern Buzzes will have a heat lamp at their disposal for convenience). Unlike Bori, Buzz are ectotherms or “cold-blooded.” This means that they let the environment dictate their internal body temperatures. One benefit of this strategy is that, by not maintaining a core temperature, they use far less energy. It is said that Buzz can survive days without food because of this (although they surely would enjoy a more consistent food source, if available!) But this adaptation is not without drawbacks: Buzz do not enjoy the cold, and can become quite sluggish with prolonged exposure. Even with added winter layers, they still find the winter to be difficult and will often walk rather than fly when temperatures plummet. Some companies have even developed wing warmers to keep these fragile appendages from facing frost bite. Population Ecology This branch of Ecology focuses on the trends of one species over time. Specifically, what causes the ups and downs, and any patterns of life history within the population. We tend to focus on the population structure (such as how abundant they are or how their population is distributed) as well as population growth, decline, and growth rates. Here, we have two populations of trees in the Neopia Central Research Forest. Biologists counted the number of trees belonging to a certain age for two species: Oaks and Maples.

In the Maple tree population, we note that most of the population is young and that fewer trees are living to an old age. This could be due to a number of factors, including natural senescence, disease, and a major disturbance event. If, in fact, the trees became old after 5 years, we would expect fewer individuals after this point. Other research done in forests around Neopia have shown that maples can live upwards to 15 years. It is possible that the environmental conditions are not optimal for Maples in Neopia Central. Additionally, there was a Maple Blight that hit the population 9 years back, which knocked back many of the young trees. And 7 years ago, a major drought hit the area, causing some trees to wither or be more susceptible to disease.

Unlike the Maple population, Neopia Central Oaks are skewed towards an older population. A Mutant Kookith invasion caused by the Petpet trade has caused issues for tree regrowth in this area. Mutant Kookith tear up the bark and unearth saplings with a diameter of less than 8cm. The Petpet Protection League has been working with biologists to humanely relocate and rehome the rogue Petpets, but Kookith population continue to climb faster than that of control efforts. Local botanists are concerned that without protective measures for the young trees that there will no restorative growth and that the area may be devoid of Oak trees in the future. Population size is limited by resources. When a population approaches the maximum level that is maintained with the available resources, this is the “carrying capacity.” Population size often hovers around carrying capacity and is self-correcting. We often see this with wild Petpet populations. When available food supplies decline, so does their carrying capacity; it is a dynamic number, ever responding to the whims of the environment in which they dwell. Community Ecology This branch of ecology looks at the interactions between all of the biotic or living factors in a system. A few examples of this include predator-prey relations, mutualism, and competition. Predator-Prey Interactions of Lupe and Chia The Lupe-Chia system is well known and well-studied from data sets going back over one century. As with all predator-prey systems, population sizes of both sides fluctuate. When Chia populations are higher, Lupe populations respond with greater success, thus increasing as well. There is, however, a lag between prey and predator population increases. And likewise, when predator populations increase, Chia populations decrease, and so it continues. But the Chia does not simply roll over and give up; prey species have developed all manner of defences. In the case of Chia, a species that is not very quick-footed, crypsis and aposematic colouring are both common. Crypsis is a form of camouflage where the prey species imitates something else to avoid detection. Fruits and vegetables are common, but there is also a camouflage colour that mimics mossy vegetation and vines. Aposematic or warning colouring is used when the prey wants to send a signal to the predator. What signal, you ask? One of danger. Some Chia, such as the fire Chia, eat fire apples, which gives them a very foul taste, while others such as the disco Chia, are known to break out in groovy and totally far out music at frequencies that cause pain to the Lupe’s sensitive ears. Beyond these two signal-based defences, there are also anatomical defences such as barbs, quills, and spikes. Some Petpet examples of this include the Splyke, Morkou, and Roburg 3T3. When threatened, the Morkou rolls into a ball, exposing a wall of spikes. Roburg 3T3 have a similar strategy, shutting its body within a hard, barbed shell. Splyke eject poisonous barbs that are hard to remove when angered or frightened, and are among a number of species that use chemical defences to avoid predation. Even Petpetpets have defences; Scribblet are known to jab any potential predators with their quilled heads. Of course, none of these defence strategies come without a cost. Energy that is funnelled into defence is removed from daily living expenses. And if a prey species needs to avoid feeding for safety or find safer places to graze, then it will be obtaining less energy than it would without the presence of a predator. Mutualism Mutualism involves the partnership of two species for their shared benefit. There are two types of mutualism: obligate and facultative. Obligate mutualism means that their relationship is dependent on one another, that without one partner, the other would struggle, if not go extinct all together. Facultative mutualism is a beneficial relationship that is not required for the continued existence of both partners. One well-studied system is the yucca flower and a Petpetpet known as a Ditrey. These P3 lay their eggs on the plant, and in return, they are key in the pollination of their host. Ditrey are the only known pollinators of the yucca, and they are most successful when they lay their eggs on the yucca. Carmariller and Beekadoodle are both pollinators for a number of flowers in Neopia. They gain nectar from their various hosts and in return, aid in pollination. But, generally speaking, these two species of petpets are generalists and flit among a large variety of different of species. Carmariller tend to be attracted to bright colours, some of which shows most clearly in ultraviolet (beyond the perception of most Neopian species). Some flower species even have “nectar guides” to aid in Carmarillers finding them and landing in the correct place. In some cases, pollinators have special beaks that are specially attuned to one species of flower. Beekadoodles have long, straw-like beaks that best suit trumpet-shaped flowers. We call these relationship patterns pollination “syndromes,” and it has to do with the patterns of pollination based on the size, colour, and smell of the flowers. Competition Competition is an interaction where two individuals (this can be within the same species or two different species) fight over the same resources. This is a lose-lose situation for everyone involved. Energy spent fighting is energy not used towards surviving. Over time, similar species tend to specialize to avoid resource overlap. Fleeper and Tuceet, for example, eat different sized seeds. Fleeper beaks are better at accessing smaller seeds while Tuceet can break larger seeds. By resource partitioning, or spreading out the kinds of food sources that they enjoy, both species can maximize their energy input and minimize energy loss due to competition. Ecosystem Ecology Ecosystem Ecology involves the dynamic interactions of all the living and non-living factors within a system. This may involve the transfer of energy up food chains as well as the effects of nutrients. Food Chains and Energy A food chain is the simplified flowchart of who eats whom, but there are limits to how many links are in a chain. As you jump one link, only about 10% of the energy gained from eating is used for growth and survival. The rest is lost to heat and a number of biological processes. Even the Flat Apple Tree only uses a fraction of the energy it receives from the sun to grow its apples. Bear in mind, the system depicted below is a terrestrial (land-based) one. There are typically fewer links on land because there are more endotherms involved. Within aquatic systems, which contain mostly ectotherms, phytoplankton (which are autotrophs that photosynthesize) make up the basis of the food chain, and there are a number of zooplankton, fish, and aquatic Petpet species that comprise the links above them.

Not all primary production comes from the sun, as Dr. Zo Ez’s team discovered. There is a second system at the bottom of the ocean, one based on sulfurous vents. Specially adapted motes live there in large numbers. To quote her Y20, 17th Day of Hiding interview, “These motes are really chill because they live at the bottom of the Maraquan Sea, so low metabolisms all around. They feed off positive sea energy and glow brighter when the ocean conditions are better…. The motes depend on sulfur-fixing bacteria to provide food and light. In return, the motes offer a safe place to stay. One must have the other or they cannot persist.” The abiotic (non-living) conditions of a habitat are critical for determining what species can realistically survive where. Depending on the types of creatures that inhabit the system, there may be more or less links up the food chain. A few ecosystem examples include the riparian forests (close proximity of a stream) of Meridell or the harsh desert of the Sakmet delta region. Nutrients Nutrients are the chemical components used as building blocks for life. Phosphorous, nitrogen, and carbon are just a few of these. All of these nutrients cycle in dynamic ways so that they are always present in the environment. Whichever nutrient is least common tends to be the limiting factor in an aquatic environments, usually phosphorous. Conclusions Neopia hosts an incredible diversity of life. Within its biosphere is a huge combination of habitats and environments, which allow for species adapted to them to thrive. What mysteries are awaiting discovery? How will we maintain these habitats in the neopocene (a geological era where our actions define the biggest ecological changes)? These are all topics of intense discussion and debate. But learning how organisms are suited to their environment, how they interact with their own species as well as other species, and what nutrients they require to survive, are all critical information to craft solid, well researched management plans. Until next time, thank you for joining us on another edition of “Science with the Seekers.” Acknowledgements We would like to thank the following researchers for sharing their expertise: Dr. Quinn Corvus, Dr. Zo Ez, Dr. Luca DeVale, Dr. Jay Blue, and Melody Harvester, M.S.

|